All three steps of SFRA entail review, evaluation and challenge. Politicians, leaders and managers will be experienced in evaluating the issues and the options: reviewing the expected impact, the risks, the available timeframe, the likely support, the likely opposition, the costs involved, the feasibility, the disruption involved.

However, reviewing corruption reduction strategies are also different from normal programmes. SFRA proposes that this leading should review the options by challenging them in the following ways:

Challenge dialectically

To avoid having a long list of desired actions in your strategy, force the choices. This is where you ‘pick the right battles, ignoring lesser objectives’. SFRA helps to narrow down the choices that you have through a dialectic approach: offering contradictory choices which you then choose between, knowing your own situation. Here are ten dialectical choices:

1. Incremental progress or large-scale change?

It is well-known that most corruption problems are more complex to solve than you expect, involving as they do a range of stakeholders and often some political choices. It also may be sensible for other reasons: to see how one reform measure turns out before you move on to the next, or as a way for you and your team to learn the mechanics of implementing corruption reforms with an ‘easy’ first few tasks before taking on larger challenges. Another good reason is that if you are within a ministry and there is no major political angle to the changes, then the corruption reforms will probably best happen the same way that most improvement reforms happen inside large organisations – slowly and steadily.

Multilateral organisations usually advise that you should choose incremental change. Here for example is the EU, in their toolbox for practitioners engaged in public administration reform: ‘An incremental approach, with provision for feedback and adjustment along the way, may reduce uncertainty and thus opposition. This process of

continual change tallies with the concept of ‘obliquity’, which recognises that

goals are often achieved indirectly, not as intended. Senior public servants, either elected or appointed, set out the reform objectives as the overall direction of travel, the administration makes steps towards the desired destination, and takes the most appropriate paths on the way, learning from experience: there is no precise road map to the future’ (EU 2017 p211).

But there are also some powerful arguments for the alternative approach. When there is a political dimension to the corruption issues and a political opening happens, you may have that one chance to make a significant change. This is especially the case when there are large changes such as an election, or the disgrace of a major political figure, or a national disaster aggravated by corruption. Such openings will not stay that open for long.

In the same vein, if your anti-corruption messages are part of the reason for being in power, you have to show rapid change – even if not on fundamental issues – before the electorate becomes too disappointed. Equally, even without any disruptive event, if you have strong alignment between key groups of stakeholders on particular corruption issues, you may be able to make rapid major change that will melt away as the alignment fades or some other priority takes centre stage.

There are also arguments for large-scale change when there is no major political angle. Staff in large organisations can become expert at subverting change initiatives, whether in a top-flight first world commercial organisation or in an Afghan ministry. They know how the changes are supposed to work and they know how to seem to cooperate, how to delay, how to sow the seeds of internal dissent, how to ensure the first few steps fail, and other ways to kill the initiative.

I have personally seen major change initiatives fail in similar ways in both such types of organisations. So, making a large, sudden step-change can be a smart way to avoid such subversion. This could be on a micro scale, such as secret planning to remove the chief corruption perpetrator inside a directorate, or on a larger scale such as cutting off large pieces of a Ministry so that each can be tackled as smaller fiefdoms. The successful national-level corruption reforms in Georgia and Estonia were both through large-scale, rapid change.

There is also an in-between strategy: to start with small changes so as to build momentum and credibility, moving on to larger change projects if the first smaller ones go well and/or if opportunities emerge for a sudden larger change. Academic research has identified this approach as the more common route to success: ‘change will occur gradually and punctuated equilibria will be the rule’ (Mungiu-Pippidi and Johnston 2017, p76).

2. Preventive strategy or disciplining strategy?

The quick answer to this choice is that a preventive strategy is better, easier and cheaper. A good example would be e-procurement, which is showing huge results in reducing corruption in multiple sectors. There are also no situations where a purely disciplining strategy has been seen to be successful. That said, you have to have discipline options available, and these require some thought.

First, prosecutions: this is less of a choice than it looks when working within a sector, for the simple reason that you have little control over the way the country’s investigative and prosecution process operates. You have one big lever – to recommend staff, contractors or others for investigation and prosecution when this has not been the habit of the organisation in the past – but that’s about it.

Second, sanctions and dismissal of staff: This is a crucial area for you to examine, because such discipline measures have often become less and less used. There can be different reasons for this – the procedures are slow and cumbersome, or they are biased in favour of certain groups, or they have been marginalised with insufficient, poor quality staff, and so on – but you should plan so that some of your reform measures address how they can be strengthened or used more effectively. Another example would be implementing a robust disciplinary code, with a clear outlawing of corrupt actions, that all within a sector agree to abide by (e.g. doctors or teachers).

3. Prioritise fighting corruption or building integrity?

There has long been discussion over whether active anti-corruption measures – such as controls and sanctions – are more or less effective than measures that promote and incentivise good behaviour by individuals. The simplest and most common answer is that both are necessary, which we agree with, and this means that the question becomes one of striking the right balance between them. This will vary between cultures.

Being explicit about corruption has advantages. In some countries the word ‘corruption’ is easily used in public, discussed and argued over. But in other countries the word corruption has only the most negative connotations, of possible personal involvement and therefore likely punishment and disgrace, and few leaderships would want to lead an ‘anti-corruption’. In other countries it is not only a sensitive topic, but one that is also personally dangerous.

Building integrity therefore sounds like a better choice. Integrity is an attractive personal attribute, and much more motivating than the negatively-loaded ‘reducing corruption’. Behavioural research also shows that people respond well to appeals to their integrity. This can be an inconspicuous message, such as “thank you for your honesty”.

Such moral appeal has been shown to be even more effective than a reminder of the threat imposed by a punishment. These findings are in line with the understanding that most people view themselves as moral individuals. ‘When reminded of moral standards, actions are adjusted accordingly to reduce the dissonance between self-concept and behaviour’ (OECD Colombia report 2017, p70).

However, there are also disadvantages to an integrity-focused approach. Using nice words like ‘Improved governance’ and ‘Integrity’ when you really mean tackling corruption can demonstrate immediately a lack of political energy to tackle the real problem, or a justification for more technical reforms such as process improvement, rather than tackling the tougher sides of the problems. Integrity measures – capacity building, training, codes of behaviour and so forth – can appear insubstantial and often focus on areas where it is hard to demonstrate impact. Sometimes, the word ‘integrity’ does not always translate well: there is no equivalent word for integrity in Slavic languages, for example

So, there are two distinct issues here. One is the balance you choose between the two approaches. The other is how you want to ‘brand’ the initiative. Is it best to be seen as ‘tough’, with an anti-corruption message, even though there may be plenty of integrity focused measures? Or do you want to show that the initiative is a positive, motivating one? There is no right answer. In the defence sector, for example, NATO chose a message of ‘Building Integrity’, as did the Defence Ministry of Saudi Arabia, whilst the Ukraine and Afghan Defence Ministries chose messages of Anti-Corruption (Pyman 2017).

This same choice exists for strategies at the national level. Out of 41 national anti-corruption strategies reviewed recently more than half have an approach of preventing corruption only. Eleven plans referred in some significant capacity to both preventing corruption and building integrity as a dual-approach to anti-corruption. Only one country strategy, Taiwan, had a tone that focused primarily on integrity. The other balance of note was a combination of preventing corruption and ‘promoting transparency’ in Estonia, Lithuania and Turkey (Pyman et al 2017).

4. Focus on daily corruption or high-level corruption?

In developed countries there is usually little daily corruption, so this choice has an easy answer. In developing countries, however, both are prevalent, and often the two are linked because the corrupt high-level groups control hierarchies of bribery that go all the way down the levels of the organisation to extracting money from citizens.

This is a big and tricky strategic question. If your answer is ‘both’, then you risk having such a range of objectives as to be unlikely to succeed at any. However, there can be a more nuanced answer. A strategy can have a number of public-facing elements which are easier to achieve, whilst at the same time having some lower profile, slower reforms that will have a longer-term impact. An example is given in the health sector, where a public-facing reform is to reduce corruption in surgery waiting lists, and a substantive reform is to put in place a proper stock management system of medicines.

5. Engage the public immediately, or keep public expectations low? Engage closely with the media, or keep them at arm’s length?

This is a critical topic that can make or break the initiative. For example, an analysis of 471 NGO anti-corruption projects showed that the most significant indicator of success or failure was whether the media were integrally engaged in the project from the start or not. In a government context it is a complex question with a whole ‘communications plan’ of its own, depends on the nature of the media in the country, as well as on the nature of the reform objective and plans. It is an area to ask for the assistance of any communication professionals that you have in your organisation.

6. Narrow focus, such as on a single reform, or broad?

As with the choice between corruption and integrity, there are two distinct issues here. One is the balance you choose between a narrow initiative and a broad one, and the important aspect of not having too many priorities.

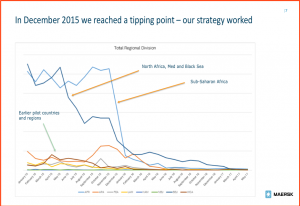

Example: Private sector narrow priority. There is a nice example in the private sector, where the shipping giant Maersk wanted to stop its ships’ captains paying bribes as their container ship entered ports. They took many actions, but the most prominent was to install an IT system that was used on every ship and into which the captains recorded all bribes paid. The graph of progress (the number of bribes paid, aggregated across all ships, plotted against time) was a stunning, convincing way to demonstrate the reform (Feb 2018, published with permission of Maersk).

Example: Private sector narrow priority. There is a nice example in the private sector, where the shipping giant Maersk wanted to stop its ships’ captains paying bribes as their container ship entered ports. They took many actions, but the most prominent was to install an IT system that was used on every ship and into which the captains recorded all bribes paid. The graph of progress (the number of bribes paid, aggregated across all ships, plotted against time) was a stunning, convincing way to demonstrate the reform (Feb 2018, published with permission of Maersk).

Example: Using the ‘fix-rate as a single indicator of success. This is an anti-corruption metric developed by the NGO Integrity Action, working with local communities in developing countries. The Fix-Rate measures the extent to which anti-corruption, transparency and accountability tools and laws are used to resolve a problem to the satisfaction of key stakeholders. The focus is on measuring deliverables to citizens (outputs) and to assess whether remedial action helped to achieve a specific fix. The Fix-Rate is the percentage of identified problems that are resolved. For example, if community monitors identify problems in ten projects and resolve six of them, they have achieved a 60% Fix-Rate. If they resolve only two problems, their Fix-Rate is 20%. Integrity Action, working with local councils, have tested the fix-rate metric in Afghanistan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Nepal, Palestine and Timor Leste.

The second issue is how you want to ‘brand’ the initiative. Is it best to be seen as focusing on a single key issue – promising to solve it – or do you want to show that you are addressing the corruption problems ‘thoroughly’, covering all the worst issues? Again, there is no ‘right’ answer. For example, in the same study of 41 country strategies already referred to, 33 of the strategies were broad in scope and 8 were narrow in scope.

7. Substantive reforms or giving people hope?

This is a choice because officials are often drawn to substantive reforms, but they have a nasty habit of turning out to be expensive, slow and not delivering what was hoped for. Similarly, reformers in other countries that have been slower getting their reforms underway, despite having a strong mandate against corruption, have lost momentum. The Bulgarian government of 2009-2013 was one such example (

Pyman and Tzvetkova 2013). Therefore, going for simpler reforms, often unkindly called ‘cherry-picking’ can be a better choice, because they give people hope that corruption reduction is actually possible. Especially in countries and sectors where the government is very bureaucratic and rule-bound the chance of a technocratic change being successful is low and people know this.

8. Substantive reforms or improving monitoring?

This is a slightly different choice: the drawbacks of substantive reforms are similar to the above case, but the alternative is instead to focus on strengthening ways of monitoring and responding to cases. People are realistic, and they know when a system is inflexible, so they may respond more positively if it becomes clear that individual grievances and abuses of the system are being flagged up and more actively addressed. This could be as simple as the CEO of the organisation and his leadership team being available for one whole day every week to hear the complaints citizens.

9. Improving service delivery or on saving money?

Citizens may say they want both, but they are most likely to want improved service delivery. Yet, for example in health, there are often huge sums of money to be saved for reuse in the national health system by reducing corruption in procurement, in medicine pricing, in reducing unnecessary operations, in illicit resale of products and drugs, in health insurance scams. Establishing an anti-corruption programme involves recognising this complexity.

10. Controlled execution of the plan or permitting multiple paths to reform?

Most formal plans set out a range of actions and/or projects, all to be carried out in some specified way. However, such formality conceals the fact that this is usually not how change actually happens: people will interpret and react to the changes in many different ways and it may be a better strategy to allow and indeed encourage such variation. For example, you might set some fixed policies at central level, then allow extensive variation and improvisation across the organisation. This approach, sometimes called a ‘complexity approach’, has been in vogue in large corporations for some time, but is also relevant in societal change. For example, allow separate teams to choose how they carry out the project in their area: or implement different reforms in different cities or provinces. On a larger scale, recent research suggests that encouraging such variation and diversity may be one of the reasons why China has been able to develop so quickly (Ang 2017).

Another approach to encouraging variation and thereby to increase political momentum is to have a strategy focused on networks, utilising them to create space for reform. You focus less on specific reforms and the political dynamics of effecting those reforms and instead focus on creating more flexibility and more space so that there are more possibilities that can emerge from however the political dynamics evolve. The way that the political dynamics evolve – or are encouraged to evolve – is through networks, especially by working with those who act as the connecting nodes within networks. See, for example, Andrews 2008 Creating space for political engagement in development.

Challenge politically

You are likely to know the political context, but it can be valuable to consider this in more granular detail. Who may be gaining from each corruption issue, and why? Who might gain and who might lose from reducing corruption in this specific area? What are the sources of leverage are there for the reform group? What advantages might they have that they can use?Argument over the gaining, losing and sharing of benefits is the essence of politics. The argument and the resistance is all the greater when the benefits are illicit ones – ‘rent-seeking’, in the language of economists.

Sometimes, doing a Political Economy Analysis (PEA) helps to address these issues, and lays them out in a structured way, so as to help decide which corruption types to address and how. Reformers can do such an analysis themselves, or can commission someone to do it more formally. There are many guides available, such as those from Hudson et al. (2016), ESID (2015) and Whaites (2017).

The supposed need for ‘political will’ is generally an unhelpful way to frame any strategy for change. Whilst strong political support is a benefit, it is still a remarkably hard task to implement corruption reform. Even where you do not have top-level political will, each sector will still contain many people committed to working for reform and to improve outcomes. The purpose of the strategy-formulation process in such situations is to identify ways to progress despite the lack of top-level political commitment. Reformers have shown that tactical reforms can occur successfully under conditions of limited political will, even in the most unfavourable situations of endemic corruption or violence, such as the improvements in public procurement in Ukraine and Afghanistan.

The impact of national regime type

Prussia’s, China’s, and Vietnam’s very top-down, pretty militaristic, and very rigid development strategies – have been relatively successful: At least in repeat of economic growth and indicators like health, though not on other criteria such as human rights or voice for minorities. Similarly, a top-down regime like China can implement a massive anti-corruption campaign and do it with scant regard to procedural fairness or rule of law. These contrast with the more participatory, worker- and-religious reformer driven movements of, say, the UK, which also resulted in reform but by following a very different path.

Though this is a vast oversimplification of the different routes that countries stake too modernity, it shows clearly that regime type matters.

A good and unusual example of this, where the same reform was implemented in two different political regimes is that of I-Paid-A-Bribe, a website created in India for collating petty bribery reports. It had a significant effect in India. Chinese online users copied the website, but they failed after three months, not only because of state repression, but also because Chinese netizens didn’t know how to be responsible, civic users of a democratic initiative. Yuen Yuen Ang (2014) has done a detailed comparative analysis of how the differing contexts led to the failure of I-paid-a-bribe in China.

Another way of examining this is to look at the effect of different regimes in a corruption context. Johnston was the pioneer of such analyses, where he concludes that there were four distinct syndromes of corruption, each associated with different political regimes (Johnston 2008, 2012):

| Syndrome |

Political regime |

Examples |

| Influence markets |

Mature democracies |

US, Japan, France, Uruguay |

| Elite cartels |

Consolidated/reforming democracies |

Italy, Argentina, South Africa |

| Oligarchs and clans |

Transitional regimes |

Russia, Philippines, Mexico |

| Official moguls |

Undemocratic |

China, Kenya, Indonesia |

Examine the differential influence of regime type across sectors

The analysis from Khan et al (2016) indicates that there are different corruption syndromes for different industries within a single country. He illustrates this with four case studies of the different corruption regimes: three different industries in Bangladesh (power, garments, electronics) where the different industry structures led to quite different sorts of corruption, and a fourth one in the Land Administration.

Examine whether the features & incentives of the sector are fully reflected in the options

This is a core belief of this website. Each sector is very different, with quite different incentives. Furthermore, corruption types that can seem to be a generic issue – nepotism, say, or small bribes for low level service delivery – may manifest differently in different sectors, and the ways it can be addressed are also likely to be markedly different. Dealing with nepotism in the education sector, for instance, will likely require a different approach from nepotism in the police services.

Political will considerations

‘Political will’ is a phrase usually heard in a binary form: On the one hand it is ‘the essential ingredient for any success to occur’, whilst in other analyses the frequency with which it is invoked correlates with its absence. Vague statements of poetical are made when anti-corruption strategies have been put together without regard to the political feasibility of the reform measures, and without regard to how political support for any particular measure might be generated.

A major part of any strategy is exactly about this; how you can generate sufficient political enthusiasm for your reforms, as we have already been discussing above. Sometimes there are special situations, notably in high corruption environments, where all forms of political will are problematic. Another useful perspective comes from defence sector reform in Poland; when you have high political support, go for the reforms that are most fundamental and hardest for successor politicians to undo (Wnuk).

Nonetheless, bureaucracies and officials sometimes have a lethargy and an aversion to taking any risks that just seems impossible to shift, despite all the best efforts of you and your colleagues and any amounts of political will.

In such cases, you need to re-look at the reform ideas and the reform strategy. Maybe you need to be less ambitious. Or to focus on just one thing. Or to encourage outside groups, like civic groups or civil society to try to develop the reform momentum instead of you. In extremis, there may be nothing else to do but to wait for some more promising circumstances.  This is actually a common way for progress to happen: people wait for more auspicious circumstances and when they arrive they recognise the chance and are quick to act: the academics call such moments ‘punctuated equilibrium’ or ‘critical junctures’

This is actually a common way for progress to happen: people wait for more auspicious circumstances and when they arrive they recognise the chance and are quick to act: the academics call such moments ‘punctuated equilibrium’ or ‘critical junctures’

There is a good recent report from the Developmental Leadership Program (2018) on understanding politics and political will as the process of making change, called ‘Inside the black box of political will’.

The political value of very small first steps

Corruption is a subject where, to use a British phrase, it is very easy to ‘frighten the horses’. Thus, one review element is whether the approach can be sequenced in a way that starts with unthreatening change.

An example of this experience from Pyman was the early years of the Transparency International Defence & Security Programme, when it started collaborating with NATO on anti-corruption. After much discussion of the momentousness of the change for NATO and multiple large committees considering the engagement, the first NATO actions were the drafting of a handbook of good anti-corruption practice and developing a methodology for integrity peer reviews of NATO partner countries. Despite the disappointment of the TI folk, the modesty of these initial actions was most probably the right strategy, as it allowed the subject to percolate into the machinery of NATO despite widespread nervousness, and thereby to grow over time into an established part of NATO’s desired capabilities.

The opportunities posed in times of major disturbance to the social equilibrium

At such times, the normal reluctance to change may be replaced by a willingness to accept extraordinarily rapid change. For example, some of the most dramatic reductions of national corruption, such as in Georgia and Estonia, happened because the political leaders believed – rightly – that their people were ready for rapid, radical action against corruption, and that the usual political circumstances provided an opportunity; even whilst the outside specialists were advising a slow, cautious approach. If this is present in your situation, then any of the normal guidance on how to do corruption reform do not apply.

Better understanding the types of power in shaping an environment

Power helps individuals, organisations and coalitions to shape their environment. It is a positive and productive force, not negative and controlling. power seriously means you should take time to recognise its different forms. Analysing power means identifying the powerful individuals who get to decide at key decision-making points − so-called visible power. Second, it can mean identifying who or what sets the decision-making agenda. For example, hidden power can determine what issues are taken off the agenda behind closed doors and never openly debated or voted on. Or third, the most structural and ‘insidious’ form of power is that which shapes people’s desires, values and ideological beliefs in the first place. Invisible power like this can influence people without them even realising it. For example, the acceptance of gender roles such as authority to speak in public meetings, by both men and women, is a deeply ingrained and unquestioned form of power in many societies.

Maximising collaborations and coalitions of parties with different interests

For sizeable reforms that involve political accommodation and negotiation among parties with different interests, you should think what sort of a group you could bring together. Here is a good example from the health sector in the Philippines that illustrates how it can be done.

A diverse range of partners, including doctors and health-related organisations, led reform against tobacco, via the so-called ‘Sin tax’. It was a classic coalition of parties with different interests. The reform coalition included diverse components, namely:

- ‘reform entrepreneurs’, activists, experts, policy wonks from the world of civil society, NGOs, and academe;

- reform ‘champions’ from within the administration, in departments, agencies, and the Office of the President;

- reform ‘champions’ within Congress;

- advocacy groups, allied associations, organizations, and pressure groups;

- media outlets: investigative journalists, reporters, social media and Internet websites.

Plus, there were also ‘allies of convenience’. The reform coalition also found itself in alignment with British American Tobacco (BAT) and San Miguel Corporation, which openly sought to ‘reform’ a tiered tax classification scheme which inhibited the entry of its products into a market monopolised by others.

This example is quoted in Development Leadership Programme (2018) Inside the black box of political will.

In the event, the passage of the bill secured billions of pesos in annual new tax revenue for the government and contributed to growing investor confidence in the Philippines. The Sin Tax Reforms had significant health implications as well. The passage of the bill has also helped to strengthen the political capacities, knowledge, and connections among a network of ‘reform entrepreneurs’ within the administration, in Congress, and in civil society.

Test the options against your sources of advantage

Like the availability of large scale training capability in the Ukraine example mentioned earlier in this section, organisatons have all sorts of features that can be turned to advantage when seeking to reduce corruption. The biggest of them all is to tap into the pride and professionalism of the various professions working in the sector. Most professuonals want to do a good job, and look on in despair when their organisation is viewed as corrupt. Thus possible sources of advantage need to be considered explicitly at this stage of reviewing the reform options.

Challenge the plans

Work up the options to check if the plans are feasible

A statement of the blindingly obvious: Strategy is about action, getting from current state A to desired state B. None of the reform options can be considered ready for decision unless an outline plan has been develped to show how the individual elements are going to be put into place. Sadly, this vital step is ignored in most strategies. The error has grown up that strategy is somehow too broad/grand/conceptual to require basic testing on how it can be implemented

Review flexibility

Military generals are very eloquent on the limits of planning. Almost two hundred years ago, the German war thinker Carl von Clausewitz said, in words that could equally apply to anti-corruption: “War is the realm of uncertainty: there quarters of the factors on which actions in war are based are wrapped in a fog of uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgement is called for, a skilled intelligence to accent out the truth.”

There is no ‘procedure’ that will resolve this uncertainty for you. But here is guidance on what we suggest you do:

- Work hard at defining a few robust ‘objectives’, as discussed in 1. above. You want your core objectives to be memorable, easily communicable to be people, and likely to remain unchanged even if lots of circumstances change.

- Don’t be afraid to have a ‘simple’ core strategy.

- Conversely, avoid as much as possible having a monster strategy in which you plan to change everything. Government bureaucracies and development agencies are both very prone to these sorts of horrors, because officials feel there is safety in covering ‘everything’. Do not do this!

- Improvisaton is part of strategy, not a denial of it. There is good theory behind this seemingly-stupid statement. An alternative view of strategy is that a formal strategic plan can be a threat, because it reduces the chance of learning when key assumptions are no longer working. This does not mean anarchy, it simply means that the amount of order is deliberately under-specified. People easily miss the point that a little bit of order can go a long way. For example, a clear statement of purpose in a commercial organisation is a powerful symbol that that may give sufficient sense of direction to all the senior executives in the organisation. The same can be true of anti-corruption strategies that have a single very strong sense of direction, such as happened in Georgia or Estonia. This line of thinking about strategy has become more common in the last few decades and is sometimes called ‘Emergent strategy’. For some of the original thinking about this approach, see Weick (2001) p350ff, and for a more recent critique see Freedman 2013, p555ff.

- Convene a small group of people to be your strategic thinking group, with whom you routinely discuss how the overall strategy is going. This would usually not be part of the formal governance structures that are monitoring progress, but something less formal, more able to see the overall picture.

Be clear about your timeframe

There are three timeframes to establish: 1) the timeframe of the overall programme, 2) the timeframe within which you need results to be appreciable to the public, and 3) the timeframe of each individual element of the programme. If you are developing the sector strategy for a Ministry, the timeframe would normally be shorter, 2-3 years, because of the imperative to show results within the lifetime of the Parliament. If it is a department or division initiative, the timeframe will commonly be 18 months to 2 years. Be attentive to the timing of the electoral cycle. Most reform programs slow down about twelve months ahead of the upcoming elections, and the newly elected government may also ditch your plans.

Skills, motivations & diversity

The match with the political skills of your team and collaborators

Besides convincing people to support your reforms because of your common purpose and because your ideas are the right ones, you are also seeking to achieve your reforms by judicious influencing and political skill. You may well have these skills yourself. But do also considering specifically finding people with such skills and bringing them on board, who are familiar with how to build support and pull together coalitions. They might exist within your own organisation or ministry, but there are also many people who have specialised in this sort of role.

For example, in the reform of the ‘Sin tax’ in the Philippines, quoted above in Section 3.1.2, a sophisticated coalition was put together involving parliamentarians and companies and the ministry and civil society. The core strength of the coalition came from established advocacy groups and experienced activists. These groups and activists used highly labour-intensive, specialised and complex forms of mobilisation. Thus, this campaign was able to attract people who were almost ‘professionals’ at building such coalitions.

Leveraging emotional motivations to build support

The above situations are large-scale initiatives, but for many reformers the issues are more about persuading particular individuals, or groups of individuals to support the changes and/or to stop active opposition.

Mark Pyman’s experience in the military sector was that officers were much readier to work ‘with the grain’ of the reforms than was expected. People within and outside of individual military forces anticipated wholesale rejection of corruption reform plans by military officers, but this often proved not to be the case. In general, the reason was simple. Officers around the world have similar professional training as cadets – like at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in the UK. A core part of the training is that you must have, and show, integrity if you are to be credible as a leader of soldiers. Most officers have deeply internalised this training, and they recognise the conflict if the military culture they are in obliges them into corrupt practices. It therefore takes less persuasion than you would expect to persuade them to assist in the reforms, even if the benefits will only be felt by the next generation of officers. Their caveat, in cooperating, is that the reforms should not be aimed at personal charges against them. For more on this, see Pyman (2017) Addressing corruption in military institutions.

That’s not rocket science, and you and your colleagues should similarly be looking for the motivations that would persuade the groups you are working with – whether engineers, doctors, nurses, teachers, police officers, business executives or others – to support the planned reforms.

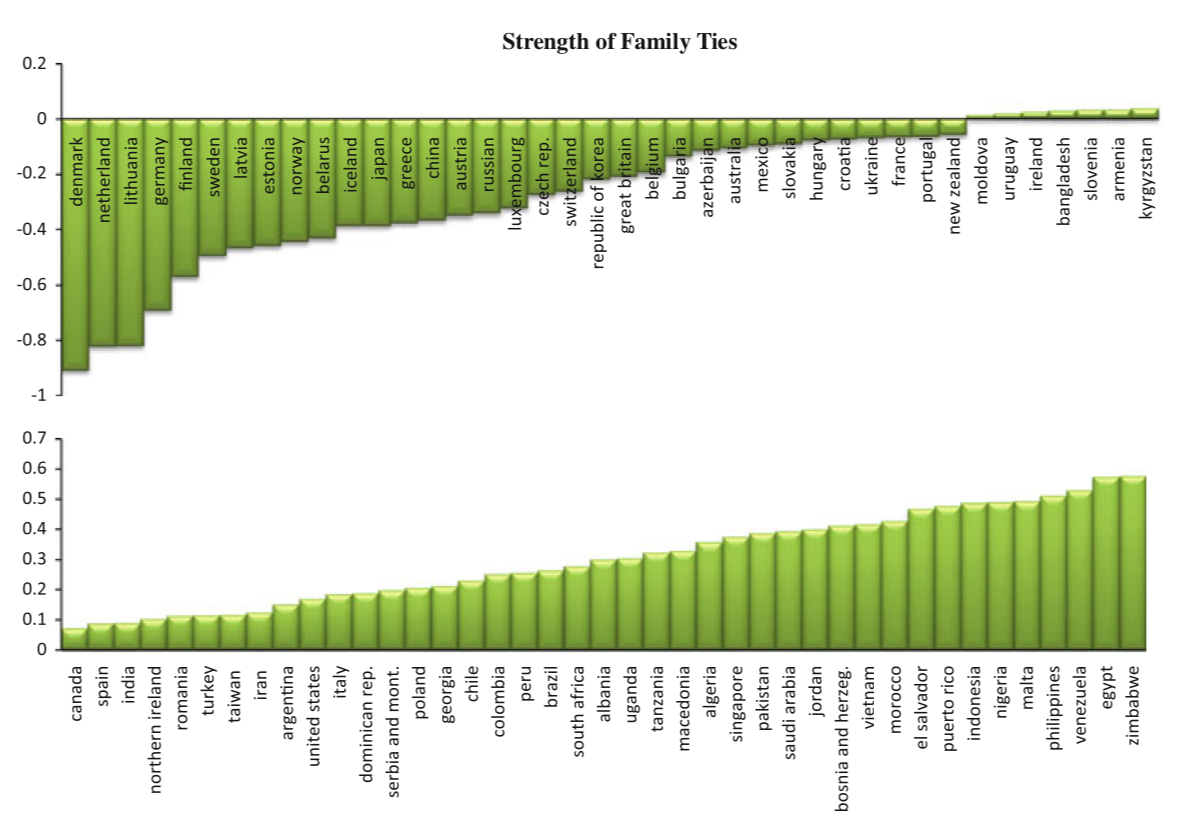

The strength of family ties is an important shaping factor

Some reform approaches are founded on the presence of strong links between individuals in communities. A example would be the oversight impact of parent committees in schools. Conversely, where the community links are weaker, other measures – such as central oversight agencies – may have better chances of success.

The strength of such ties varies widely from country to country and region to region, according to research. In some countries, family ties seem to form only a modest part of the social context, such as in Denmark, Japan and China. At the other end of the spectrum family ties are extraordinarily strong, such as in Zimbabwe, Egypt and Venezuela. See the diagram below, from Alesina and Giuliano 2010.

The strength of family ties. Source: Alesina and Giuliano (2010)

The strength of family ties. Source: Alesina and Giuliano (2010)

Test with diverse groups, especially women and youth

Much though we may wish, it is not possible to prescribe a ‘procedure’ for taking context into account. The best generic advice we can offer is this:

- Contextual issues often surface best in discussion. Be sure to discuss the choices with colleagues and stakeholders.

- Test your initiative with one or more groups of youngsters. They can have a perspective that is free of some of the constraints of ‘context’.

- Test your initiative against what you expect to be the challenges of political supporters and opponents, using the results of any political economy analysis you have done.

- Be aware of your particular context at every step of your approach. Ask yourself, as you read about each corruption type and each reform example, if there are elements of context that are like yours and ask yourself how the context differs.

Challenge Programme Management

When engineers have a large task, such as building a ship or a power station, they plan the work into many small projects, each of which is individually managed. The engineers then manage the totality of these projects as a single ‘programme’, with one master plan of how all the individual projects fit together, depend on one another, and so on. Each separate project – which for our purposes is an individual reform – might be managed in quite different ways: for example, a project to implement technical changes to IT systems will be managed quite differently from a project to strengthen the values of the organisation. This is ‘Programme management’. Programme management approaches are routinely used for managing organisational change programmes in government.

Managing a multitude of small projects in a coordinated way is a formal skill in its own right, so do approach this with respect as many programmes fail due to poor execution. There is plenty of guidance available on how to run a good programme, which we summarise only briefly in this section.

Common errors in programme management

If you speak to any experienced project manager, he or she will tell you that most large projects fail. The average failure rate is 70%: of every three large projects, two will fail to deliver. This is a shocking statistic, but it has been verified in hundreds of analyses. What’s more, it is equally true in the developed world as in the developing world. The safest way to avoid this risk is to make sure that your work programme is built up of many smaller pieces of work rather than a few large ones.

A clear definition of the purpose, value and scope of the programme

We have already described much of this in the sections above on developing the strategy. It is important! With a clear overall direction and purpose, you can better keep a wide range of people on a common path and can more easily re-centre the programme as time goes on and as unexpected things happen. In some programme management guides for public sector projects, you will see this referred to as the ‘business case’

Full-time project personnel

Often the most important element for a successful programme is to have a full-time programme manager and a small project management unit. This is a large investment, but it is necessary: it can be very hard to run a programme with part time inputs and coordination. This small team then monitors, coordinates and chases up all the individual actions and projects.

Programme management and control

: This is the principal task of the core personnel. They should be working to a detailed project plan, updated every week and pay attention to all the mundane but vital bits like weekly task lists, cross-programme coordination, liaison with external stakeholders, project schedules, organising steering committees, and so on.

Programme Governance

There should be a steering committee that reviews progress and direction. Depending on the size of the programme, this could be at two levels: for example, one a committee of high-level officials plus others that meets quarterly, the second a committee involving external stakeholders and politicians that meets twice per year.

Programme ownership

It is good practice for a ‘Senior Responsible Owner’ to be appointed who is the top-level person who can be considered to own the programme. He/she would normally be the Chair of the senior steering committee. He/she might be a senior politician, or the national ‘anti-corruption champion’, or a top public official

Engaging with stakeholders

There will be a multitude of different groups with an interest in the programme; meeting them regularly, communicating with them regularly, involving them at appropriate stages: all these are the task of the project management unit. For each corruption issue you should map out those who will probably object to reform, as well as those who would lose out financially or lose out in respect of services that they might be denied. Then talk with those involved in each corruption issue. It might be easy to overcome the reluctance to change. Then build collaborations and coalitions to enable those involved to cooperate. Many people are only reluctantly caught up in endemic corruption and are ready to cooperate to find a way out if they think it is safe and credible. A good example is corruption in ports, where the port authorities and the police and the customs are involved as well as the shipping companies. If all are brought together to work out how to eliminate the corruption, then it proves to be possible (see here).

For the larger-scale corruption issues, you should build an understanding of who is receiving the corrupt revenue flows. It is rarely one person but a hierarchy or a network. You can get others to assist you in doing analyses of such networks.

Tracking results and benefits

Tracking the results and benefits is obvious, essential, and routinely not done. This task needs to be established from the beginning, either for the project management unit or, better, by another group that can view the results more independently. Using an NGO group is one possibility.

Two programme implementation tools

Programme management guidance from the UK. Governments in some countries have formal units and guides on how to set up and structure good quality programmes. The UK, for example, has an agency of the Cabinet Office called the “Infrastructure and Projects Authority’, whose purpose is to provide independent assurance on major projects (see here). It also supports colleagues across departments to build skills and improve the way we manage and deliver projects. Their predecessor organisation developed a formal qualification in project management called ‘PRINCE2’ – for all sorts of projects from IT and construction projects at one extreme to social change projects at the other – that is used extensively across the UK government (see here).

Implementation guidance from UNODC. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has produced a document entitled National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation. This is a detailed report about the process of strategy-making and implementation. It covers assigning responsibility for drafting the strategy to a small, semi-autonomous group; ensuring the continued support and involvement of senior political leaders; consulting regularly with all government agencies that will be affected by the strategy; soliciting the views of the political opposition whenever possible; engaging all sectors of society in the drafting process; emphasizing communication, transparency and outreach throughout the drafting process; allocating sufficient time and resources to drafting the strategy; and taking advantage of other countries’ expertise (UNODC 2015).

Challenge governance & alignment

Strengthening the initiative using formal mechanisms in government and among stakeholders

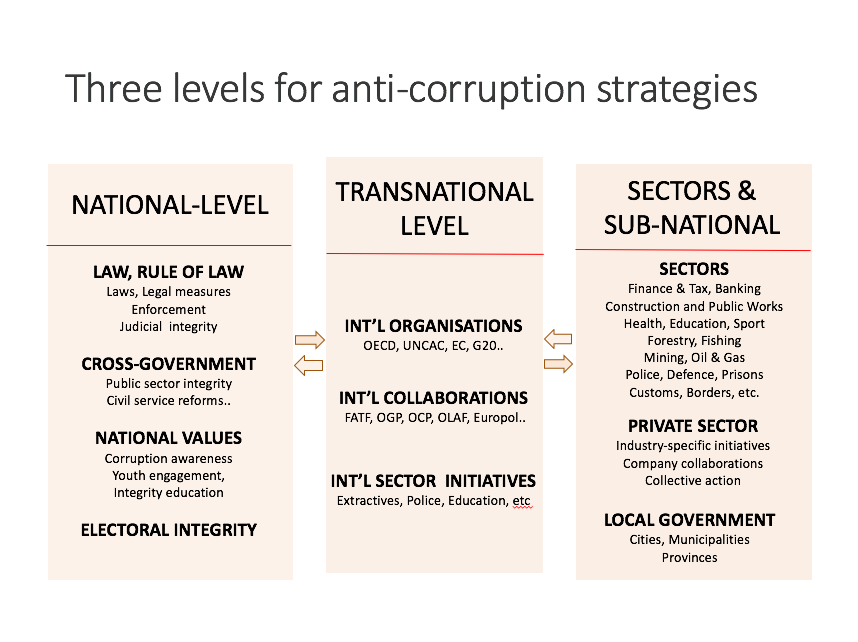

One of the lessons learnt about tackling corrruption is that to do corruption reforms ‘on their own’ is usually a recipe for failure. At the very least, they should be embedded in the organisation’s overall programmes. Usually it makes sense that they be included in larger cross-organisation alignments. A good exammple is the sector-specific reforms that form part of the UK Government’s National Anti-Corruption Strategy and how they are drawn into the overall coordination (HM Government 2020). Note, though, government coordination mechanisms can be so labyrinthine, and/or predestined to fail, that it may be better to stay outside of them.

You will normally expect to have a greater chance of success and more sustainability if your efforts are aligned to the wider government effort. This is especially the case if the government has got a broader anti-corruption plan running and is pursuing progress on it across multiple sectors.

A comprehensive government-wide anti-corruption strategy would embrace national, sub-national and sector strategies, as per the diagram opposite. Ideally your sector strategy would fit cleanly into an overall structure along these lines.

But on the whole, government anti-corruption efforts across ministries are not well aligned. In such cases you could also consider setting up an informal coordinating forum across Ministries.

Decide whether cross-government alignment is a worthwhile effort

Nevertheless, there is a prior decision to consider: you may not want to focus on cross-government alignment, but to operate this plan within your ministry and independent of the rest of your government. This might be the best way to proceed, if for example your ministry is doing much more than other ministries, or if the rest of government has other priorities. It is also possible that the rest of government does not yet have a strategy or is taking its time. In this case, we suggest that you go ahead regardless. There is also the risk that working together with the rest of government will mean ceding some control of the programme to the central unit, and that your own efforts may be diluted or lost. I and others working in anti-corruption have seen this happen several times.

On the other hand, it helps if the strategy has authority as an official document of government, which can be useful in building more support: official plans and strategies act as a common point of reference across all the different Ministries, agencies and related organisations. You should be able to use this authority in persuading other parts of the ministry and other parts of government to support it.

Countries have shown they can make progress via a more coordinated effort of sector strategies across ministries. For example, Poland is one country that has made significant progress against corruption in the period 2005-2013 (see diagram); one of the Ministries that led these efforts was the defence ministry.

Take advantage of any central cross-government coordination unit

Governments are always limited in personnel, and they often look to set up anti-corruption strategies without any champion and without any coordinating or monitoring unit. Our belief is that this is a guarantee of failure of the strategy. If there is a champion and a full-time unit, they may or may not be effective, but at least there is a chance. If your government has such a unit, then do ensure that your ministry team engages with them. If it is all being done without dedicated personnel, then you may be better off pressing ahead on your own. Some countries have set up active coordinating mechanisms and staff for coordinating their anti-corruption actions across government ministries. For example, the UK (see here), Bulgaria in the period 2009-2013 (see here) and Afghanistan (see here and a UN evaluation here).

Strengthen alignment with major government policies

There is also a policy aspect. Corruption types differ in how much they distort the policies necessary for achieving important policy goals of the Ministry and the government. Policy goals such as poverty reduction, increasing tax collection or improving national reputation can be subverted by modest levels of corruption: examples include building permit corruption and nepotism in the appointment of teachers. This is a good reason for strong coordination at policy level between ministry anti-corruption initiatives and policy makers. For more analysis of policy distortion, see Khan et al (2016); Anti-corruption in adverse contexts: a strategic approach.

Strengthen alignment with other stakeholders

Your plans may also involve close working with politicians, with Parliament, with companies, with international organisations, with civil society and others. These all take effort to engage with, but it is a core part of building support and coalitions. This is where key helpers, with deep experience of working with such groups, may be able to help you, as discussed in the section above.